Existentialist psychiatrist and theorist, considered the most important and distinguished phenomenological psychologist. In this PsychologyOnline article, we will pay tribute to a great author of the Personality Theories in Psychology: Ludwig Binswanger.

Index

- Intro: Ellen West

- Biography

- Theory

- Phenomenology

- Existence

- Dasein

- Launch

- Anxiety

- Guilt

- Death

- Authenticity

- Existential Analysis

- Therapy

- Difficulties

- Readings

Introduction: Ellen West.

Ellen West was always a little weird. She was a "bow tie" eating and put up great resistance to anyone who tried to force her to eat something that she did not like. In fact, her stubbornness was what kept her on her feet. She always had to be the first in everything she liked and she couldn't bear to get sick and stay home. In her teens, her motto was "Either Caesar or nothing!" But nothing would prepare her family for what was to come.

Being 17 years old, her poetry began to take a curious turn. In one of those poems, called

At 20, she takes a trip to Sicily. During this time, she eats a lot and gains some weight, which her friend makes fun of, to which she responds with big binges on food. She then begins to obsessing over the idea of being fat; she hates herself for it and begins to regard death as a cure to her misfortune.

For a short time, she recovers by leaning on work and comes out of her depression, but she always carries with her a feeling of dread. She actively turns to social changes, although she secretly considers herself to be of no use.

When her parents interfere with her engagement with a student, she plummets and returns from a resort. emaciated and sick, although she considers this obsession with being thin to be really the path to her health! When her doctor advises him to rest and he regains her weight, she becomes discouraged and has a hard time returning to her previous emaciated state.

At 28, she marries her cousin in the hope that her marriage will help him get rid of his "fixed idea" of her. After an abortionshe, she has to face the dilemma of wanting a child and at the same time not wanting to eat food typical of pregnant women. At 35, Ellen takes between 60 and 70 vegetable laxative pills during the day; she vomits during the night and has diarrhea the rest of the time. She stays at 92 pounds and looks like a living skeleton.

It is in these moments where she decides to go to a psychiatrist... and then to another. She makes two unsuccessful suicide attempts and is finally transferred to the Kreuzlingen Sanatorium, where she settles quite well in the company of her husband and under the tutelage and care of Ludwig Binswanger. Through a maintenance diet and sedatives, he slowly recovers physically, but still feels an oppressive sense of fear.

As she keeps trying to kill herself, both she and her husband are faced with a serious choice: she or she is confined to a "permanent surveillance", where she would deteriorate inexorably, or is given the high. Both decided to discharge.

When she makes this decision, Ellen feels much more recovered, since she knows what she will do. She begins to eat happily, even some chocolates and she feels full for the first time in thirteen years. She talks to her husband, writes some letters to friends, and takes a lethal dose of poison.

Why this sad story is one of the most famous clinical cases among students it is not so surprising (anorexia is not, unfortunately, so uncommon) not even because of the very particular course of events, but because of the Ellen West's ability to express her perspective on her own problem and the fact that her psychiatrist, Ludwig Binswanger, adopted a very close listening of her patient.

Let's see another of his poem

I would like to die like the bird does

Who opens his throat in great joy;

And not live like the worm that lives on land

Getting old and ugly, monotonous and silly!

No, feel for once how the forces in me ignite

And wildly be consumed by my own fire.

At some point in her childhood, Ellen divided her life into two opposing camps: on the one hand there is the "sepulchral world", which includes their physical and social existence. Her body with her low needs distracted him from her purposes. She gets old every day. Their society is bourgeois and corrupt. The people around him don't seem to care about all the evil and suffering. In the sepulchral world everything degenerates and is degenerate, everything is drawn downwards, towards the grave, towards a black hole.

On the other hand is the "ethereal world", the world of the soul, pure and clean, a world where needs are completed, where actions happen effortlessly, where there is no material resistance. In the ethereal world we can be free and fly.

There are some people who try to ignore the "ethereal world". They are not comfortable with the anxieties and responsibilities that come with freedom. Some prefer rather to be told what to do, so that they join a sect or gang or a multinational corporation. But even so, they continue to feel fearful, because they know that this is not right. They do not live their life, therefore they will never be happy.

Others they look for a direction in their body. They begin by looking for simple pleasures, but soon find that they become tiresome. So they try another drug or a new perversion or something else. After a while, this doesn't satisfy either. They fail, not because the pleasures do not give pleasure, but because there is only a part of themselves in the pleasures sought.

Ellen West tried to ignore the "sepulchral world." I wanted to fly beyond the material and mundane into the ethereal, into the good, right, and pure. And, in a small domain, she came close to achieving it: she managed to shrink her body down to a skeleton, but it's never enough.

We cannot ignore a part of who we are by searching for another part. You cannot ignore your body or your soul, any other aspect of who you are. Like it or not we are both bird and worm. Any other issue is not just non-human; it is simply nothing!

Biography.

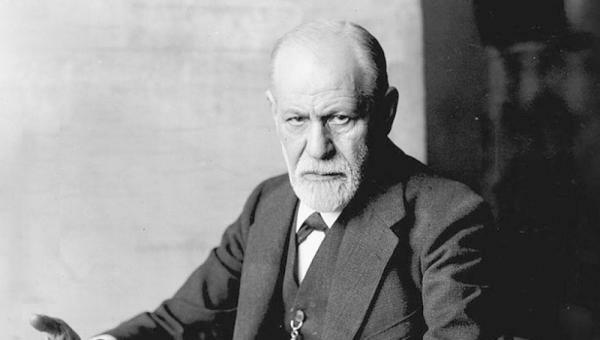

Ludwig Binswanger was born on April 13, 1881 in Kreuzlingen, Switzerland, into a fairly well-off family in the medical and psychiatric tradition. He obtained his BA from the University of Zurich in 1907. He studied under the tutelage of Carl Jung and as he himself was doing his internship with Eugen Bleuler, sharing his interest in schizophrenia.

Jung introduced him to Sigmund Freud in 1907. In 1911 Binswanger held the position of Chief Medical Officer and Director at the Bellevue Sanitarium in Kreuzlingen, a position previously held by his father and his grandfather. The following year, he fell ill and received a visit from Freud, who rarely left Vienna. Their friendship lasted until Freud's death in 1939, even despite their theoretical differences. In the early 1920s, Binswanger developed a special interest in the works of Edmund Husserl, Martin Heidegger and Martin Buber, gradually leaning towards an existentialist perspective rather than Freudian. In the 1930s, we could frankly say that he was the first truly existential therapist. In 1943, he published his most important work, Grundformen und Erkenntnis menschlichen Daseins, which has not yet been translated into English.

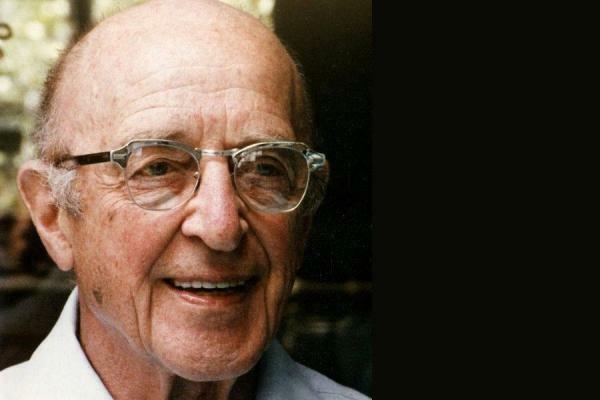

In 1956, Binswanger left his position at Bellevue after 45 years as Chief Medical Officer and Director. He continued to study and write until his death in 1966.

Theory.

The existential psychology (or existentialist), as well as the Freudian, is a "school of thought", a theoretical tradition, of research and practice that many people dedicate themselves to, but he differentiates them that in the first there is no sole founder. In fact, existential psychology has its roots in the work of a diverse group of philosophers in the second half of the nineteenth century, especially Soren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietsche.

Both were as different as day and night, so it is somewhat difficult to imagine a school derived from the conjunction of the two.

Kierkegaard he was interested in recovering the depth of faith from the dry Copenhagen religion of those days, and Nietzsche, on the contrary, he is famous for his famous exclamation "God is dead!"; although it is true that they were more different from the philosophers who preceded him than among themselves. Both approached philosophy from the point of departure of real people, passionately involved in the difficulties of everyday life. They both believed that human existence could not be limited to complex rational systems, be they religious or philosophical. Both were closer to being poets than logicians.

Since Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, very few philosophers, and more recently a few psychologists, have attempted to clarify, extend, and promote the ideas of existentialism. Unfortunately, many have not been very good poets, so dedicating reading to them is not usually very pleasant, rather painful. But we must bear in mind that these people have been fighting against a stream of centuries of highly systematic, rational and logical philosophy and against a psychology reduced to physiology and behavior. What they want to convey is often perceived as odd, precisely because we are used to traditional logic and science.

Phenomenology.

The phenomenology is a thorough and careful study of the phenomena and it is basically an invention of the philosopher Edmund Husserl. The phenomena are constituted by the content of consciousness, things, qualities, relationships, events, thoughts, images, memories, fantasies, feelings, acts, etc., that we experience. Phenomenology is an attempt to allow these experiences to "speak" to us, to live them, so that we can describe them in the most impartial way possible.

If you are one of those who has been studying experimental psychology, this could be another way of talking about objectivity. In experimental psychology, as well as science in general, we try to get rid of subjectivity and see things as they really are. But phenomenologists would suggest that you cannot get rid of subjectivity, even if you insist on doing so. The true attempt to be a scientist means approaching things from a particular point of view, that of a scientist. We cannot put aside subjectivity since it is not something separate, at all, from objectivity.

Modern philosophy in almost all its extension and including the philosophy of science, is dualistic. This means that it separates the world into two parts, the objective part, usually conceived as the material part, and the subjective or conscious part. So our experiences would be an interaction between these subjective and objective parts. Modern science has leaned towards this position, emphasizing the objective, the material part, and downplaying the subjective part. Some call the conscious an "epiphenomenon," or a minor by-product of brain chemistry and other material processes; something more like a nuisance. Others, like B.F. Skinner, they don't even consider consciousness as something.

Phenomenologists consider this to be a mistake. Everything a scientist deals with comes "through" consciousness. Everything we experience is colored by the "subjective". But a better way to put it would be that there is no experience that does not understand as much what we have experienced as what is experienced. This idea is called intentionality.

So phenomenology asks us to leave what we are studying, whether it be a thing out there or an internal feeling or someone else's, or human existence, and let us reveal. We can do this by being open to experience, without denying what is there because it does not fit our philosophical or psychological ideas or our religious beliefs. In particular, it asks us to let's separate or put in parentheses the question of the objective reality of experience, what reality is really. Although what we are studying seems to be more than what we are experiencing, it is nothing more than what we are experiencing.

Phenomenology is also an interpersonal task. While experimental psychology can utilize a group of subjects in such a way that subjectivity can be removed from their experiences statistically, phenomenology can use a group of co-investigators so that their perspectives can be grouped together to gain a richer and fuller understanding of the phenomenon. We call this intersubjectivity.

This method, as well as its adaptations, has been used to study different emotions, psychopathologies, things like separation, solitude and solidarity, artistic and religious experience, silence and speech, perception and behavior, etc. It has also been used to study human existence itself, most notably by Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre. And this is the very basis of existentialism.

Existence.

On one occasion Kierkeggard compares us to God, and of course, we lose. Traditionally, we view God as omnipresent, omnipotent, and eternal. We, on the other hand, are abysmally ignorant, ridiculously weak, and too deadly. Our limitations are clear.

Many times we want to be a little more like God, or at least like the angels. Angels are supposedly not as ignorant and weak as we are, and they are immortal! But, as Mark Twain pointed out, if we were angels, we wouldn't recognize ourselves. Angels do nothing but carry out orders from God. They cannot do otherwise. They are simply the so-called "messengers" of the Lord and nothing more and nothing less than for all eternity!

A table is more like an angel than we are. The table has a nature, a purpose, an essence, which we have given it. He is there to serve us in a certain way, as an angel serves God.

Groundhogs are like this too. They also have a plan, a purpose, a blueprint, if you will, in their genetics. They do what their instincts tell them to do. They rarely require any kind of teaching.

Maybe it could be a sad thing to be a board or a groundhog, or an angel, but of course it's easy! We could say that their essence is before their existence: what they are is before what they do.

But, existentialists say, this is not so for us. "Our existence precedes our essence", as Sartre said. I don't know what I'm here for until I've lived my life. My life, what I am, is not determined by God, by the Forces of Nature, by my genetics, by my society, or even by my family. Each of them could provide me with the basic materials to become what I am, but it is what I choose to be in life that makes me me. I believe myself.

If the scientist is the model of humanity for George Kelly and the cognocivist psychologists, the artist is the model of the existentialists.

We could say that the essence of humanity (what we all share and make us different from the rest of the things in the world) is our lack of essence, our Liberty. We cannot be captured by a philosophical system or a psychological theory; We cannot be reduced to physical and chemical processes; our futures cannot be predicted with social statistics. Some of us are men, some of us are women; some of us are black, others white; some of us come from one culture, others from another; Some of us have imperfections and others have different ones. The "basic materials" differ dramatically, but we all share the task of making ourselves.

Dasein.

Binswangger adopted the terms and concepts introduced by the philosopher Martin Heidegger. The first and most important of the terms is Dasein (literally, being there) that many existentialists refer to when talking about human existence. Although, as we have said literally means "to be there", it carries with it other subtle connotations: the term original in German suggests a continuous existence or continuity of existence, survival, persistence. Furthermore, the emphasis on the "gives" or "there" part has the sense of being in the middle of everything, in the thick of things. Also this emphasis has the sense of being there as the opposite of being here, as if we were not where we belong; as if we were more directed towards something else.

Although there is no precise translation of the term, many people use the word existence or human existence. Existence is derived from the Latin existare, which means the fact of existing; life of man and by opposition to essence, concrete reality of any being. As can be seen, this definition carries with it some of the concepts underlying the word dasein: to be different, to go beyond oneself, to be again.

There are still other meanings for Dasein: Heidegger referred to it as opening (Lichtung), like meadow, opening in the forest, since Dasein is what allows the world to reveal itself. Sartre also shares this sense of openness, referring to human existence as the nothing. In the same way that the hole exists only by virtue of something solid, Dasein stands in sharp contrast to the "tightness" of everything else.

The main quality of Dasein, following Heidegger, is the careful (attention) (Sorge). "Being there" is never a matter of indifference. We are constantly involved in the world, in others and in ourselves. We are committed or involved with life. We can do many things, but neglect is not one of them.

Launch.

The launch it refers to the fact that we are "thrown" into a universe that we have not chosen. When we begin to choose our lives, we begin with many choices made for us: genetics, environment, society, family... all those "basic materials". A better way to understand this would be to consider that "I" conscious and free, I am not separate from the "that", physical and determined.

Let's think about example in our body. On the one hand, we are our body, our body is us. When we want to, we walk, or talk, or look, or listen. We perceive, think, feel and act "with it", "through" it. It is very difficult to conceive of life without it. But at the same time it is like any other "thing". You can resist; it can fail us; we can lose a member; We can get sick and lose this or another function, but we are still ourselves. Sometimes the world enters us, as for example if an artificial heart or a heart valve is inserted. Other times we reach out into the world, using a telescope, a telephone, or a rod. We are trapped in the world and the world in us and there is no way of knowing where one ends and the other begins.

Launch also refers to the fact that we are born into a pre-established social world. Our society precedes us, as well as our culture, our language, our mothers and our fathers. In our helplessness, as infants and children, we must depend on them.

Even as adults, we depend on others. Sometimes we "fall victim to" the "Other", that faceless generalization we often call" people "(as when we say" people are looking at ") or at the" we "(as when we affirm" we don't do that ") or at the" them "(" They don't like anything that"). We pay with our freedom and we allow ourselves to be enslaved by our society. This is called Drop.

Binswanger, following the philosopher Martin Buber, adds a more positive note to the idea of falling: he applies it to the notion of "spaciousness" towards others (I-towards you) and to love. If Dasein is an opening, we can open ourselves to others. We are not "locked in" in ourselves as some existentialists seem to suggest. Binswanger perceives this potential as an intrinsic part of Dasein, and even grants him a special place by referring to him as being-beyond-the-world.

Anxiety.

Existentialists are famous for pointing out that life is hard. The physical world provides us with both pain and pleasure; the social can lead to anguish and loneliness as well as love and affection; and the personal world, prevalently, contains anxiety and guilt within it, as well as an awareness of our own mortality. And these questions, difficult to bear and not mere possibilities in life, are inevitable.

Being free means creating opportunities. In fact, we are "condemned" to choose, as Sartre put it, and the only thing we cannot choose is not to choose. Even, as Kierkegaard pointed out, we have to choose what we think; we are in fact ignorant, weak and mortal; That is, we will never have enough information to make a good decision, we can hardly ever carry it out when we think we are ready, and we will die before we make it!

Kierkegaard, Heidegger, and other existentialists use the word Angst, Anxiety, to refer to the apprehension we feel when we move towards the uncertainty of our future. It is sometimes translated as dread to emphasize the anguish and unease that comes with the need to choose, but anxiety is the word that most globalizes the concept. Anxiety, unlike fear or dread, does not have a well-defined object. It is more of a state of being than anything else more specific.

Existentialists often speak of the nothing In relation to anxiety: Since we are not like tables, angels and marmots, preciously determined, sometimes we feel as if we are going to fall into nothingness. We would like to be rocks (solid, simple, eternal), but we realize that we are whirlpools. Anxiety is not a temporary inconvenience that a friendly therapist can take away from us; it's part of being human.

Fault.

It seems then that existentialism is not an "easy" philosophy. It provides very few ways of avoiding the responsibilities derived from the actions themselves. We cannot blame our environment, our genetics, or our parents, or such a psychiatric illness, or alcohol and drugs, or pressure from my partner, or the Devil himself.

Heidegger uses the German word Schuld to refer to responsibility to ourselves and it means both guilt What debt. If we don't do what we know we should do, we feel guilty; we have acquired a debt with our potential. And since Dasein is always a question of potential, by natural principle it will never be fully satisfied. Therefore, to some extent we will always be "in debt" to Dasein.

Another word that fits well here is remorse. Guilt is certainly a matter of regret over those things we have done (or failed to do) harmful to others. But we also feel remorse about past decisions that have not hurt others but have hurt ourselves. When we have chosen the easy path, either we have not committed to ourselves or others, or we have decided to do less instead of more; When we have lost our nerve (momentum), we feel remorse.

Death.

Existentialists are sometimes criticized for their preoccupation with death. It is true that they do in fact discuss the subject in greater depth than most theorists, but not with morbid interest. It is by facing death that we can come to an understanding of life. In his play The flies, Sartre say what "life begins beyond hopelessness."

Heidegger calls us be-towards-death. It seems that we are the only creature aware of its own end And when we realize this, we try to get it out of our minds by working or doing anything else in the social world. But this does not help us. To evade death is to evade life.

Once I realized that while I was holding my daughter in my arms she was thinking about death (maybe it is something strange, but thinking about these things helps me in my life work). When I brought her sleeping face to mine, I thought how soon both she and I would die. At the time I was overwhelmed by my love for her. It is precisely because we have so little time together that love goes beyond a simple family arrangement. When you are truly aware that you are going to die, every moment you lose is lost forever.

Authenticity.

Unlike other personality theorists, existentialists make no effort to avoid value judgments. Phenomenologically, the good and the bad are as "real" as solid residue or burnt toast. So they are clear that there are better and worse ways to live life. The best forms are associated with the term authentic.

Living authentically implies being aware of oneself, of our circumstances (launch), of our social world (fall), of our duty to create ourselves (understanding, understanding), of the inevitability of anxiety, guilt and death. Further, it means accepting these things as an act of self-affirmation. It involves commitment, compassion, and participation.

Note that the ideal of mental health is not pleasure or even happiness, although existentialists have precisely nothing against these things. The goal is to do what you can do the most or what you do best.

Inauthenticity (Falsehood)

Someone who is not authentic is no longer "growing", he is simply "is". The opening has changed for the lock, the dynamic for the static, the possibilities for current events. If authenticity is movement, this person has simply stopped.

Existentialists avoid classifications. Each person is unique. In principle, we start with different "basic materials" (genetics, culture, families, and so on). Then from these bases we begin to create ourselves by virtue of the choices we make. Consequently, there are as many ways to be authentic as there are people, as well as not to be.

The conventionality it is the most common way of not being authentic. It includes ignorance of one's own freedom and of living a conformist life and superficial materialism. If you manage to be like anyone else, you will not need to choose or create choices. You can go to the authority, or your partner or advertising to "guide" you. Then you will fall into what Sartre called bad faith.

Another form of inauthenticity is existential neurosis. In a way, the neurotic is more attentive than the conventional person: he knows that they are faced with choices to make and is frightened by this. In fact, it scares him so much that he becomes oversaturated. He is dumbfounded or panicked, or exchanges his existential anxiety and guilt for an anxious and guilty neurosis: he finds something "less strong" phobic, an obsession or compulsion, a target for his anger, a disease or the pretense of a disease) to make the difficulties of his lifetime. An existential psychologist would say that although you can get rid of symptoms with a number of techniques, in the end you will have to face the reality of Dasein.

Binswanger views inauthenticity as a matter of choosing a simple theme in life, or even a small number of themes that allow the rest of Dasein to be dominated by them. Those subjects who possess a personality that Freudians call "anal-retentive", for For example, he may be dominated by a theme of "retain" or "hold within one", or of rigidity or perfection. The one who does not feel in control of his life may be dominated by a theme of luck, or of destiny or of waiting. A person who eats anxiously may be dominated by a theme of emptiness and the need to fill himself. A workaholic may be dominated by a topic related to wasting time or getting over it.

Existential Analysis.

Diagnosis

Binswanger and other existential psychologists focus on discovering their client's vision of your world (or world design). It is not necessarily a matter of discussing the subject's religion or philosophy of life. What Binswanger wants to know is your "Lebenswelt", Husserl's word for "the lived world" (In this sense, in Spanish we can use the word "experience" or the "world experienced" to express the connotation of emotional experience of the subject about what he has lived. N.T.). Ultimately, the author seeks that specific point of view of his daily life.

For example, I would try to understand how you see your Unwelt or physical world (things, buildings, trees, furniture, gravity ...)

He would also like to understand your Mitwelt, or social world: your relationships with other individuals, with your community, with your culture and so on.

And I would finally try to understand your Eigenwelt or personal world. This includes both your mind and your body, as long as you think it is an important part of your sense of who you are.

Binswanger is also interested in your relationship with him. weather. He would like to know how you perceive your past, your present and your future. Do you live more well in the past, always trying to recover those wonderful years? Or do you live in the future, always waiting and preparing for a better life? Do you perceive your life as a complex and long adventure? Or as an instant; here, now and tomorrow goodbye?

Also of interest is the way we treat the space. Is your world open or closed? Is it intimate or is it vast? Is it cozy or cold? Do you perceive your life as something in motion, as an adventure and travel issue, or do you see it from an immobile position? Of course, none of these questions mean anything by themselves, but when combined with the others through the intimate relational process of therapy, can become a great source of information.

Binswanger also talks about different modes: some people live off a single mode, alone and self-sufficient. Others live off a dual mode; More like a "you and me" than a "me". Some live off a plural mode, thinking of themselves in terms of belonging to something larger than themselves (a nation, a religion, an organization, a culture). And there are even those who live off a anonymous mode, still, secret, hidden behind life. And most of us live in all of these modes from time to time and from place to place.

As we can see, the language of existential analysis is metaphorical. Life is too wide, too rich, to be captured by something as crude as prose. My life is certainly too rich to be framed in words that you already knew before you met me! Existential therapists allow their patients to reveal themselves, to let themselves see themselves, in their own words, in their own time space.

Existentialists might worry about your dreams, for example, but instead of interpreting them, they would ask what they mean to you. They might even suggest that you let your dreams inspire you, guide you, suggest their own meanings. They could mean nothing at all, and they could mean everything.

Therapy.

The essence of existential therapy is the therapeutic relationship between the therapist and his patient, or meeting. This is the genuine presence of one Dasein before another, an "opening" of one onto another. Unlike other more "formal" therapies, such as Freudian, or more "technical" such as behavioral therapy, existential therapy seems to depend more on you or be closer to you. The transference and the countertransference are considered proper and natural parts of the encounter; without abusing, of course and not without leaving them aside.

On the other hand, humanists would regard the existential therapist as more formal and more directive than they. In this sense, the existential therapist is more "natural" with his patient (usually quietly listening, but sometimes expressing their own opinions, experiences, and even emotions). "Being natural" also implies the recognition by the patient of his own internal differences. The therapist has the training and the experience and after all, it is the patient who presumably has the problems. Existential therapy is also considered a dialogue, and not a monologue by the therapist or the patient.

But existential analysis aims at autonomy of the patient. In the same way that we teach a child to ride a bicycle, we must hold them for a while, but eventually we will have to let them go alone. The child might fall, but if we never let go, he will never learn to ride! If the "essence" of Dasein (human being) is responsibility and freedom in one's life, then you cannot help someone to become a more complete human unless he is prepared to release him.

The most positive part of existential psychology is its insistence on the greatest possible adherence to "experiential world". In phenomenology, we have invested a lot of effort and time in a rigorous method to describe life and how it is lived. Theory, statistics, reductionism, and experiments deviate, at least for a moment. Existentialists say, first, we have to know what we are talking about!

This makes existential psychology apply naturally: it moves almost unintentionally in the field of diagnosis and psychotherapy; shows its presence in the field of education and may even one day delve into industrial and organizational psychology.

It is far less successful in respecting it as a research method. There are two psychological journals that speak of phenomenological research and a few journals dedicated to education and nursing open to it. But practically the bulk of psychology rejects it, and in a rather rude way. It is considered simply as unscientific, since it does not have to do with hypotheses or statistics and much less with dependent and independent variables or with control groups and samples random; all this makes it practically discarded for postgraduate programs, doctoral theses and master's degrees in universities.

Difficulties.

However, the difficulties for which existentialism has gained respect is not precisely because of its lack of traditional psychology in its foundations and practice. It is often believed that it is because is poorly understood or misinterpreted by the English-speaking stream of psychologists.

While it is true that new ideas are difficult to express and need new words and new ways of using the old ones, many of the terms of existential psychology are unnecessarily dark. Many of them come from philosophical traditions, probably familiar to philosophers, but not to most psychologists. Others are German or French and are very poorly translated. And some of them are just whimsical or pretentious.

What we need is a true English-speaking (and certainly Spanish) existentialist writer. After all, the language of ordinary experiences of ordinary people should be ordinary language, right? Rollo May and Víctor Frankl have made considerable effort in this regard, but much more needs to be done.

The existentialists they also tend to be a bit pushy, even to the point of arguing who among them has the "true" understanding of Husserl or Heidegger or whatever. They can gain a good pulse, especially if they establish their approach in such a way that it can be accepted into the mainstream of psychology, paying special attention to people like Alfred Adler, Erich Fromm, Carl Rogers, and other theorists, researchers, and practitioners who are not in fact existentialists, but are often quite vocal best.

The biggest danger I think existentialists fall into is their tendency to stay in opposition to the flow. It is true that psychology has two broad "cultures", the "tough" experimentalists on the one hand and the more humanistically inclined clinicians on the other. By denigrating experimental culture, they are simply antagonizing half of psychology!

If I am a bit harsh on existential psychologists, it is partly because I am one of them. (Although my personal tendency is closer to dynamic psychology, I understand and share many of the basic questions of existentialism. N.T.). It's like patriotism: the more you love your country, the more you worry about its failings. However, I believe that existential psychology has a lot to offer. In particular, it offers a solid philosophical foundation where Adlerians and Rogerians and Neo-Freudians, as well as other marginal existentialists can develop and refine their understanding of life human.

Readings

Bingswanger's work was first presented in English by May, Angel, and Ellenberger in a volume of articles in Existence (Editorial Piados in Spanish version and translated from English). Then several items have been collected in Being-in-the-World. Much of his work remains untranslated, especially Grundformen und Erkenntnis menschlichen Daseins(The Foundations and Cognition of Human Existence). To see the English translation of the table of contents, click here.

Regarding existential psychology and philosophy in general, read Existential-Phenomenological Alternatives for Psychology, edited by Valle and King, or a classic introduction, Irrational man, by William Barrett.

If you're brave enough, you might want to try something from the great originals in phenomenology and existentialism, like Edmund Husserl or Martin Heidegger. Kierkegaard and Nietszche are fascinating, as is Jean-Paul Sartre, who offers a different version of Heidegger's existentialism.

If you need something more accessible, try A Primer in Phenomenological Psychology by Keen, Steiner's classic Martin Heidegger, Phenomenological Psychology McCall's (which has a very interesting section on Heidegger's terminology), and Exploring Phenomenology Stewart and Mickunas'. For a story on existential psychology and psychiatry, Phenomenology in Psychology and Psychiatry of Spielberg. Other existential psychologists are also mentioned in this book.

There are endless books in Spanish about various authors considered existentialists, just type in any search on the Internet the keyword "existentialism" and they will appear. (N.T). There are endless books in Spanish on various authors considered existentialists, simply type in any search engine on the Internet the keyword "existentialism" and will appear. (N.T).

This article is merely informative, in Psychology-Online we do not have the power to make a diagnosis or recommend a treatment. We invite you to go to a psychologist to treat your particular case.

If you want to read more articles similar to Personality Theories in Psychology: Ludwig Binswanger, we recommend that you enter our category of Personality.