We understand behaviorism as that branch of psychology dedicated to analyzing and trying to determine our actions, that is, our behavior. In this PsychologyOnline article, we will talk about a great exponent in the Personality Theories in Psychology: B.F. Skinner.

Index

- Biography

- Theory

- Reinforcement schemes

- Modeling

- Behavior modification

- Readings

Biography.

Burrhus Frederic Skinner was born on March 20, 1904, in the small town of Susquehanna in Pennsylvania. His father was a lawyer and his mother a smart and strong housewife. His Parenting was old-fashioned and hard-working.

Burrhus was an active, outgoing boy who loved to play outside and build things, and in fact, he liked school. However, his life was not without tragedies. In particular, his brother died at the age of 16 from a brain aneurysm.

Burrhus received his English degree from Hamilton College in upstate New York. He did not fit in very well with his years of study and did not even participate in the fraternity parties of the soccer games. He wrote for the university newspaper, including articles critical of the university, the faculty, and even against Phi Beta Kappa! To top it all off, he was an atheist (at a college that required him to attend chapel daily).

In the end, he resigned himself to writing articles on work problems and lived for a time in Greenwich Village in New York City as a "bohemian." After some travels, he decided to go back to college; this time to Harvard. He got his BA in psychology in 1930 and his Ph.D. in 1931; and he stayed there to do research until 1936.

Also this year, he moved to Minneapolis to teach at the University of Minnesota. There he met and later married Ivonne Blue. They had two daughters, the second of whom became famous as the first infant to be raised on one of Skinner's inventions: the air cradle. Although it was nothing more than a crib and playpen combination surrounded by glass and air conditioning, it seemed more like keeping a baby in an aquarium.

In 1945 he acquired the position of head of the department of psychology at Indiana University. In 1948 he was invited to return to Harvard, where he stayed for the rest of his life. He was a very active man, constantly researching and mentoring hundreds of doctoral candidates, as well as writing many books. Although he was not a successful fiction and poetry writer, he became one of our best writers on psychology, including the book Walden II, a compendium of fiction about a community driven by his behavioral principles. We will refer from here to the term behavioral, as it is more appropriate within the field of psychology. N.T.

On August 18, 1990, Skinner died of leukemia, after becoming probably the most famous psychologist since Sigmund Freud.

Theory.

The entire Skinner system is based on the operant conditioning. The organism is in the process of "operating" on the environment, which in popular terms means that it is constantly breaking in; doing what he does. During this "operability", the organism encounters a certain type of stimulus, called reinforcing stimulus, or just reinforcer. This special stimulus has the effect of increasing the operating (this is; the behavior that occurs immediately after the reinforcer). This is operant conditioning: the behavior is followed by a consequence, and the nature of the consequence modifies the organism's tendency to repeat the behavior in the future."

Imagine a rat in a box. This is a special box (called, in fact, "Skinner's box") that has a pedal or bar on one wall that when pressed, activates a mechanism that releases a pellet of food. The rat runs around the box, doing what rats do, when he "accidentally" steps on the bar and presto! The food pellet falls into the box. The operant is the behavior immediately preceding the reinforcer (the food pellet). Almost immediately, the rat steps off the pedal with its food pellets to a corner of the box.

A behavior followed by a reinforcing stimulus causes an increased probability of that behavior in the future.

What happens if we don't give the rat more balls? She is apparently not stupid and after several unsuccessful attempts she will refrain from stepping on the pedal. This is called extinction of operant conditioning.

A behavior that is no longer followed by a reinforcing stimulus causes a decreasing probability that that behavior will not occur again in the future.

Now, if we start the machine again so that when pressing the bar, the rat gets the food again, the behavior of stepping on the pedal will come up again, much faster than at the beginning of the experiment, when the rat had to learn the same for the first time. This is because the turn of the booster takes place in a historical context, going back to the first time the rat was boosted by stepping on the pedal.

Reinforcement schemes.

Skinner likes to say that he came to his various discoveries accidentally (operationally). For example, he mentions that he was "low on supplies" of food pellets, so he had to make them himself; a tedious and time consuming task. So he had to reduce the number of reinforcements he gave his rats for whatever behavior he was trying to condition. So, the rats maintained a constant and invariable behavior, neither more nor less among other things, due to these circumstances. This is how Skinner discovered the reinforcement schemes.

The continuous reinforcement is the original scenario: every time the rat commits the behavior (such as stepping on the pedal), he gets a pellet of food.

The fixed frequency program was the first that Skinner discovered: if, say, the rat steps on the pedal three times, it gets food. Or five. Or twenty. Or "x" times. There is a fixed frequency between behaviors and reinforcements: 3 to 1; 5 to 1; 20 to 1, etc. It's like a "piece rate" in industrial clothing production: you charge more the more shirts you make.

The fixed interval schedule use a contraption to measure time. If the rat presses the pedal at least once in a particular period of time (say 20 seconds), then it gets a food pellet. If he fails to carry out this action, he does not get the ball. But even if he steps on the pedal 100 times within that time frame, he won't get more than one ball! In the experiment a curious thing happens if the rat tends to take the "step": they lower the frequency of their behavior just before the boost and speed up the rate when the time is about to end up.

Skinner also talked about the programs variables. A variable frequency means that we can change the "x" each time; first press three times to get a ball, then 10, then 1, then 7 and so on. The variable interval means that we keep that period changing; first 20 seconds, then 5; then 35 and so on.

Continuing with the variable interval program, Skinner also observed in both cases that the rats did not maintain more frequency, since they could not establish the "rhythm" for much longer between behavior and reward. More interestingly, these programs were very resistant to extinction. If we stop to think about it, it really makes sense. If we haven't received a reward in a while, well, we are most likely in the "wrong" range or rate… just one more time on the pedal; Maybe this is the definitive one!

According to Skinner, this is the mechanics of the game. We may not win too often, but we never know when we will win again. It may be the next one, and if we don't roll the dice or play another hand or bet on that particular number, we will lose the prize of the century!

Modeling.

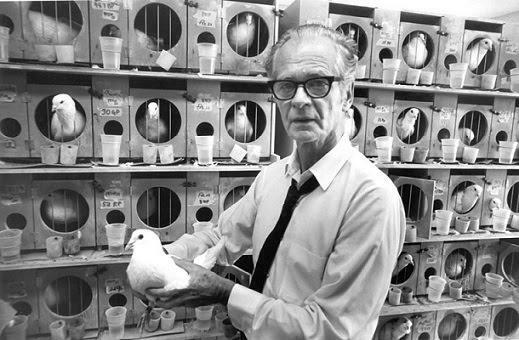

One issue Skinner had to deal with is how we get to more complex sources of behavior. He responded to this with the idea of modeling, or "the method of successive approximations". Basically, it consists in the first place of reinforcing a behavior only vaguely similar to that desired. Once it is established, we look for other variations that appear very close to what we want and so on. successively until the animal shows a behavior that would never have occurred in life ordinary. Skinner and his students have been quite successful in teaching animals to do some extraordinary things. My favorite is that of teaching pigeons to bowling!

I once used modeling on one of my daughters. He was three or four years old and afraid of going down a particular slide. So I loaded her up, put her on the lower end of the slide, and asked her if she could jump to the ground. Of course he did and I was very proud. Then I loaded it up again and put it a foot higher; I asked him if he was okay and told him to push off and drop down and then jump. So far so good. I repeated this act over and over again, getting higher and higher on the slide, not without some fear when I pulled away from her. Eventually, he was able to jump off the top and jump at the end. Unfortunately, I still couldn't climb the ladders to the top, so I was a very busy parent for a while.

This is the same method that is used in therapy called systematic desensitization, invented by another behaviorist named Joseph Wolpe. A person with a phobia (for example spiders) will be asked to place themselves in 10 scenarios with spiders and varying degrees of panic. The first will be a very soft scene (like seeing a small spider in the distance through a window). The second will be a little more threatening and so on until the number 10 will present something extremely terrifying (for example, a tarantula running across your face as you drive your car a thousand miles time!. The therapist will then teach you how to relax your muscles, which is incompatible with anxiety.) After practicing this for a few days, you go back to the therapist and both of you travel through the scenarios one by one, making sure you are relaxed, going back if necessary, until you can finally imagine the tarantula without feeling tension.

This is a technique especially close to me, as I actually had a spider phobia and was able to free myself from it with systematic desensitization. I worked it so well that after a single session (behind the original scenario and a training of muscle relaxation) I was able to go outside the house and catch one of those little leg spiders long.

Beyond these simple examples, modeling also deals with more complex behaviors. For example, you don't become a brain surgeon just by stepping into an operating room, cutting off someone's head, successfully removing a tumor, and being paid a good deal of money. Rather, you are sensitively shaped by your environment to enjoy certain things; do well in school; take some biology classes; maybe watch some medical movie; pay a visit to the hospital; enter medical school; be encouraged by someone to choose neurosurgery as a specialty and so on. This is also something your parents will carefully do, like the rat in the box, but better, the less intentional it is.

Adverse stimulus (aversive) in Ibero-American psychology the term has been translated as aversive, N.T.

A adverse stimulus it is the opposite of the reinforcing stimulus; something we notice as unpleasant or painful.

A behavior followed by an adverse stimulus results in a decreasing probability of the occurrence of that behavior in the future.

This definition describes in addition to the adverse stimulus, a form of conditioning known as punishment. If we hit the rat for doing x, he will do fewer times x. If I slap José for throwing his toys, he will throw them less and less (maybe).

On the other hand, if we remove an established adverse stimulus before the rat or José does a certain behavior, we are doing a negative reinforcement. If we cut off the electricity while the rat is standing on its hind legs, it will last longer on its feet. If you stop being heavy for him to take out the trash, he is more likely to take the trash out (maybe). We could say that it "feels so good" when the adverse stimulus stops, that this serves as a reinforcement!

A behavior followed by the cessation of the adverse stimulus results in an increased probability that this behavior will occur in the future.

Note how difficult it can be to differentiate some forms of negative from positive reinforcement. If I starve you and give you food when you do what I want, is this positive performance; is it a reinforcement?; Or is it the arrest of the negative; that is to say, of the adverse stimulus of craving?

Skinner (contrary to some stereotypes that have arisen around behaviorists) does not "condone" the use of the adverse stimulus; not because of an ethical question, but because it doesn't work well! Do you remember when I said before that José might stop throwing out the toys and that maybe I would get to throw out the garbage? It is because what has maintained the bad behaviors has not been removed, as would be the case if it had been permanently removed. This hidden reinforcement has only been "covered" by a conflicting adverse stimulus. Therefore, surely, the child (or I) would behave well; But it would still feel good to throw the toys away. All José has to do is wait until you are out of the room or find some way to blaming his brother, or somehow escaping the consequences, and back to his behavior previous. In fact, since José now only enjoys his former behavior on rare occasions, he involves a variable reinforcement scheme (program) and will be even more resistant to extinguishing said behavior!.

Behavior modification.

The behavior modification (usually known in English as mod-b) is the therapeutic technique based on Skinner's work. It is very straightforward: extinguish an undesirable behavior (by removing the reinforcement) and replace it with a desirable behavior with a reinforcement. It has been used in all kinds of psychological problems (addictions, neurosis, shyness, autism and even schizophrenia) and is particularly useful in children. There are examples of chronic psychotics who have not communicated with others for years and have been conditioned to behave in quite normal ways, such as eating with a fork and knife, dressing themselves, taking responsibility for their own personal hygiene, and the rest.

There is a variant of mod-b called token economy, which is used with great frequency in institutions such as psychiatric hospitals, juvenile homes and prisons. In these, certain rules are made explicit that must be respected; if they are, the subjects are awarded special tokens or coins that are exchangeable for free afternoons outside the institution, movies, candies, cigarettes, and so on. If the behavior becomes poor, these tokens are removed. This technique has proven especially helpful in maintaining order in these difficult institutions.

A drawback of the symbolic economy is the following: when an "intern" of one of these institutions leaves the center, they return to an environment that reinforces the behavior that initially led them to enter the same. The psychotic's family is usually quite dysfunctional. The juvenile delinquent returns directly to the "wolf's mouth". Nobody gives them tokens for behaving well. The only reinforcements could be aimed at keeping the spotlight on "acting-out" or some glory of the gang when shoplifting from a supermarket. In other words, the environment doesn't fit very well!

Walden II

Skinner began his career as an English philologist, writing poems and short stories. Of course, he has also written numerous articles and books on behaviorism. But perhaps he is most remembered by the general population for his book Walden II, where he describes an almost utopian commune operating under his principles.

Some people, especially religious rightists, attack the book saying that its ideas take away our freedom and our dignity as human beings. Skinner responded to the wave of criticism with another book (one of his best) called Beyond Freedom and Dignity. Here he asks: What do we mean when we say that we want to be free? We often want to say that we don't want to be in a society that punishes us for doing what we want to do. Well adverse stimuli don't work very well, so let's throw them away! - then we will only use reinforcements to "control" society. And if we choose the correct reinforcements, we will feel free, since we will do what we think we should do!

Same for dignity. When we say "he died with dignity", what do we mean? That he maintained "good behavior" from him for no apparent ulterior motive. In fact, he maintained his dignity since his reinforcement history led him to consider behaving in such a "dignified" way as something more reinforcing than making a scene.

The bad do the bad because the bad is compensated. The good man does good because his goodness is rewarded. There is no true freedom or dignity. Currently, our reinforcements for bad and good behaviors are chaotic and out of our control; it is a matter of having bad or good luck in our "choice" of parents, teachers, partners, and other influences. Better take control, as a society, and design our culture in such a way that the good is rewarded and the bad is extinguished. With the correct behavioral technology, we can design culture.

Both freedom and dignity are examples of what Skinner calls mentalist constructs (unobservable and therefore useless for scientific psychology). Other examples are defense mechanisms, adaptive strategies, self-actualization, the unconscious, consciousness, and even things like anger and thirst. The most important example is what he calls homunculus (Latin for "little man") that supposedly resides in all of us and is used to explain our behavior and ideas such as soul, mind, self, judgment, self and, of course, personality.

Instead of the above, Skinner recommends that psychologists focus on the observable; this is the environment and our behavior in it.

Readings

Whether you agree or not, Skinner is a good writer and very entertaining to read. I already mentioned Walden II Y Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971). The best summary of his theories is in the book About Behaviorism (1974).

This article is merely informative, in Psychology-Online we do not have the power to make a diagnosis or recommend a treatment. We invite you to go to a psychologist to treat your particular case.

If you want to read more articles similar to Personality Theories in Psychology: B.F. Skinner, we recommend that you enter our category of Personality.