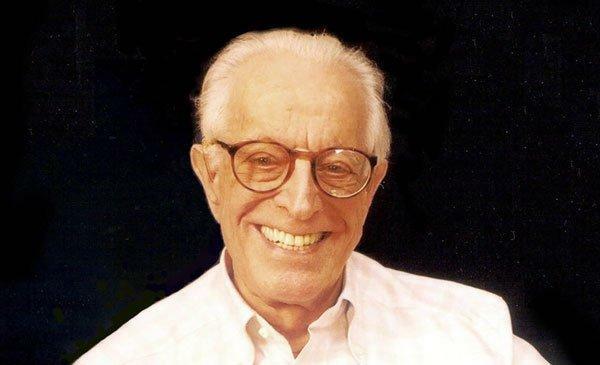

Ellis was born in Pittsburg in 1913 and raised in New York. He overcame a difficult childhood by using his head, becoming, in his own words, "a stubborn and pronounced problem solver." This time, at PsicologíaOnline, we want to highlight someone who contributed great work to Personality Theories in Psychology: Albert Ellis.

Index

- Biography

- Theory

- Twelve Irrational Ideas that Cause and Support Neurosis

- Unconditional self-acceptance

Biography.

A severe kidney problem diverted his attention from sports to books, and dissension in his family (his parents divorced him when he was 12 years old) led him to work on understanding the the rest.

At the ellis institute he focused his attention on becoming the Great American Novelist. He considered studying accounting in college; in making enough money to retire at 30 and write without the pressure of financial need. The Great Depression put an end to their longingBut he made it to college in 1934, graduating in business administration from the City University of New York. His first adventurous foray into the corporate world was that of a trouser patch business with his brother. They searched together in dress stores for all those pants that needed auctions to also adapt their customers' coats. In 1938, Albert rose to the position of director of personnel for a fledgling firm.

Ellis spent most of his spare time on write short stories, plays, novels, comic poetry, essays and non-fiction books. By the time he reached 28 years old, he had already finished at least two dozen full manuscripts, but had yet to get them published. He realized then that his future would not rest on fiction writing, so he dedicated himself exclusively to non-fiction, promoting what he would call fiction. "sexual-family revolution".

As Ellis collected more and more material from a tract called "The Case for Sexual Liberty." for Sexual Freedom), many of his friends began to regard him as something of an expert in matter. He was frequently asked for advice, and Ellis found that he loved coaching as much as writing. In 1942 he returned to college and enrolled in a clinical psychology program at Columbia University. He started his part-time clinical practice for families and as a sex counselor almost immediately after receiving his master's degree in 1943.

The moment Columbia University awarded him his doctorate in 1947, Ellis came to the conviction that psychoanalysis was the most profound and effective form of therapy. He then decided to enlist in a didactic analysis and became "a brilliant analyst in the following years." At the time, the psychoanalytic institute refused to train psychoanalysts other than doctors, but this did not prevent Ellis from finding an analyst willing to carry out his training within Karen's group Horney. Ellis completed his analysis and began practicing classical psychoanalysis under the direction of his teacher.

By the late 1940s, he was already teaching at Rutgers and New York University and was head of psychology. clinic at the New Jersey Diagnostic Center and later at the New Jersey Department of Institutions and Agencies.

But Ellis's faith in psychoanalysis quickly fell apart. He found that when he saw his clients only once a week or even every two weeks, they progressed just as well as when he saw them daily. He began to take a more active role, combining advice and direct interpretation in the same way that he did when he counseled families or on sexual problems. His patients seemed improve faster than when he used passive psychoanalytic procedures. And this without forgetting that before being in analysis, he had already worked on many of his own problems through readings and practices. philosophies of Epícteto, Marco Aurelio, Spinoza and Bertrand Russell, teaching their clients the same principles that had earned him he.

In 1955 Ellis had already completely abandoned psychoanalysis, replacing the technique with one focused on the change of people through confrontation of your irrational beliefs and persuading them to adopt rational ideas. This role made Ellis feel more comfortable, since he could be more honest with himself. "When I became rational-emotional," he once said, "my own personality processes really began to vibrate."

He published his first book on REBT. Rational Emotive Therapy) "How to Live with a Neurotic" in 1957. Two years later he formed the Institute for Rational Living, where training courses were held to teach his principles to other therapists. His first great literary success, The Art and Science of love (The Art and Science of Love), appeared in 1960 and has so far published 54 books and more than 600 articles on REBT, sex and marriage. He is currently the President of the New York Institute for Rational-Emotive Therapy, which offers a comprehensive training program and runs a large psychological clinic.

Theory.

REBT (Rational Emotional Behavior Therapy) is defined by the ABC in English. The A is designated by the activation of experiences, such as family problems, job dissatisfaction, early childhood trauma and everything that we can frame as a producer of unhappiness. The B refers to beliefs (beliefs) or ideas, basically irrational and self-accusatory that provoke current feelings of unhappiness. And the C corresponds to consequences or those neurotic symptoms and negative emotions such as depressive panic and anger, which arise from our beliefs.

Even though the activation of our experiences can be quite real and cause a great deal of pain, it is our beliefs that give it the qualification of long stay and of maintaining long-term problems term. Ellis adds a letter D and an E to the ABC: The therapist must dispute (D) irrational beliefs, so that the customer can ultimately enjoy the positive psychological effects (E) of rational ideas.

For example, "a depressed person feels sad and lonely since he mistakenly thinks he is inadequate and abandoned." At present, a depressed person can function as well as a non-depressed person, so the therapist must demonstrate to the patient his successes and attack the belief of inadequacy, rather than pouncing on the symptom itself.

Although it is not important for therapy to locate the source of these irrational beliefs, they are understood to be the result of a "philosophical conditioning", or habits not very different from the one that makes us move to pick up the phone when he rings. Later, Ellis would say that these habits are biologically programmed to be susceptible to this type of conditioning.

These beliefs take the form of absolute statements. Instead of accepting them as wishes or preferences, we make excessive demands on others, or convince ourselves that we have overwhelming needs. There are a wide variety of typical "thinking errors" that people get lost in, including ...

- Ignore the positive

- Exaggerate the negative

- Generalize

It's like denying the fact that I have some friends or that I have had a few successes. I can elaborate or exaggerate the proportion of the damage that I have suffered. I can convince myself that nobody loves me, or that I always screw up.

Twelve Irrational Ideas that Cause and Support Neurosis.

- The idea that there is a tremendous need in adults to be loved by significant others in practically any activity; instead of concentrating on your own personal respect, or seeking approval for practical purposes, and on loving instead of being loved.

- The idea of certain acts are ugly or wicked, so others must reject to the people who commit them; rather than the idea that certain acts are self-defense or antisocial, and that people who commit these acts behave in a stupid, ignorant or neurotic way, and it would be better if they received help. Behaviors like these do not make the subjects who act them corrupt.

- The idea of it's horrible when things are not the way we would like that they were; instead of considering the idea that things are very bad and therefore we should change or control adverse conditions so that they can become more satisfactory; and if this is not possible we will have to accept that some things are like this.

- The idea of human misery is caused invariably by external factors and it is imposed on us by people and events strange to us; rather than the idea that neurosis is mostly caused by our view of unfortunate conditions.

- The idea of if something is or could be dangerous or scary, we should be tremendously obsessed and outraged with it; instead of the idea that we must face the dangerous frankly and directly; and if this is not possible, accept the inevitable.

- The idea of it's easier to avoid than face life difficulties and personal responsibilities; Instead of the idea that what we call "letting it go" or "letting it go" is usually much harder in the long run.

- The idea of we absolutely need something bigger or stronger than us on which to lean; rather than the idea that it is better to take the risks of thinking and acting less reliably.

- The idea of we must always be absolutely competentintelligent and ambitious in all aspects; instead of the idea that we could have done better rather than need to always do well and accept ourselves as quite imperfect creatures, having human limitations and fallibilities.

- The idea of if something affected us considerablyIt will continue to do so throughout our lives; instead of the idea that we can learn from our past experiences without being overly attached or worried about them.

- The idea of we must have a precise and perfect control over things; instead of the idea that the world is full of probabilities and changes, and that we still have to enjoy life despite these "inconveniences."

- The idea of human happiness can be achieved through inertia and inactivity; instead of the idea that we tend to be happy when we are vitally immersed in activities aimed at creativity, or when we embark on projects beyond ourselves or give ourselves to the rest.

- The idea of we have no control over our emotions and that we cannot help feeling upset about things in life; rather than the idea that we have real control over our destructive emotions if we choose to work against the masturbatory hypothesis, which we usually encourage.

For simplicity, Ellis also mentions the three main irrational beliefs:

- "I must be incredibly competent, or else I am worthless."

- "Others should consider me; or they are absolutely stupid. "

- "The world must always provide me with happiness, or I will die."

The therapist uses his expertise to argue against these irrational ideas in therapy or, even better, leads his patient to make these arguments himself. For example, the therapist might ask ...

- Is there any evidence to support these beliefs?

- What is the evidence to confront this belief?

- What's the worst that can happen to him if he abandons this belief?

- And what is the best thing that can happen to you?

In addition to argumentation, the REBT therapist assists with any other technique that helps the patient to change her beliefs. Group therapy, unconditional positive reinforcement, providing risk-reward activities, assertiveness training, empathy training, perhaps could be used. using role-playing techniques to achieve this, promoting self-control through behavior modification techniques, systematic desensitization and so on successively.

Unconditional self-acceptance.

Ellis has been on his way to increasingly reinforce the importance of what he calls "unconditional self-acceptance". He says that in REBT, no one is rejected, even no matter how disastrous their actions are, and we must accept ourselves for who we are rather than what we have done.

One of the ways he mentions to achieve this is convince the patient of its intrinsic value as a human being. Just being alive already provides value in itself.

Ellis observes that most theories place a great deal of emphasis on the self-esteem and strength of self and similar concepts. We naturally evaluate creatures, and there is nothing wrong with this, but from the evaluation we make of our traits and actions, we come to evaluate that vague holistic entity called "self". How can we do this?; And what good does it do? Ellis thinks it only causes harm.

There are precisely the legitimate reasons for promote one's own self or ego: We want to stay alive and be healthy, we want to enjoy life and so on. But there are many other ways to promote the ego or self that is harmful, as he explains through the following examples:

- I am special or I am obnoxious.

- I must be loved or cared for.

- I must be immortal.

- I am either good or bad.

- I must prove myself.

- I must have everything I want.

Ellis firmly believes that self-evaluation leads to depression and repression, as well as the avoidance of change. The best thing for human health is that we should stop and evaluate each other!

But perhaps this idea about the ego or the self is overrated. Ellis is especially skeptical about the existence of a "true" self, like Horney or Rogers. He particularly dislikes the idea of a conflict between a self promoted by actualization versus one promoted by society. In fact, he says, nature itself and society itself rather support each other, rather than being antagonistic concepts.

Really he he does not perceive any evidence of the existence of a transpersonal self or soul. Buddhism, for example, does well without taking this into account. And Ellis is quite skeptical of the altered states of consciousness of mystical traditions and the recommendations of transpersonal psychology. In fact,he considers these states more unreal than transcendent!.

On the other hand, Ellis believes that his approach stems from the ancient Stoic tradition, supported by philosophers such as Spinoza. He also considers that there are similarities to existentialism and existential psychology. Any approach that places responsibility on the individual's shoulders with his beliefs will have commonalities with Ellis's REBT.

This article is merely informative, in Psychology-Online we do not have the power to make a diagnosis or recommend a treatment. We invite you to go to a psychologist to treat your particular case.

If you want to read more articles similar to Personality Theories in Psychology: Albert Ellis, we recommend that you enter our category of Personality.