Human beings, due to our condition as biological organisms, should maintain a natural relationship with food. The regular intake of foods rich in nutrients and in adequate quantities should constitute a universal behavior pattern between men and women.

The spectacular increase over the last decades in the number of people who show an unnatural relationship with food It has given rise to a growing interest in understanding these paradoxical behaviors and in how to help these people to regain a more appropriate eating pattern of behavior. Most start from the consideration of these behaviors as symptoms of mental disorders or illnesses labeled as anorexia and bulimia nervosa.

Index

- Existing explanatory models

- The DSM IV criteria

- Functional analysis as an etiological model of anorexia and bulimia

- Functions of reducing food intake

- Annex 1: diagnostic criteria

Existing explanatory models.

Etymologically speaking, an eating disorder would refer to all those circumstances that involve a

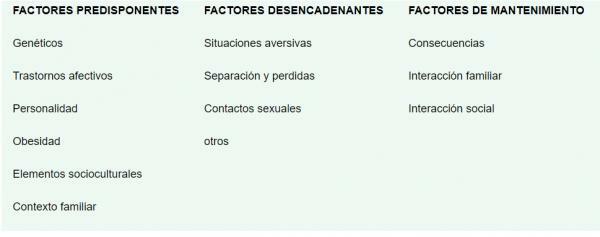

- Multidetermined Etiology Models (Toro and Vilardell, 1987) This model lists the possible causes of the problem but does not establish any type of relationship between the factors, does not speak of cause - effect relationships and only describes them.

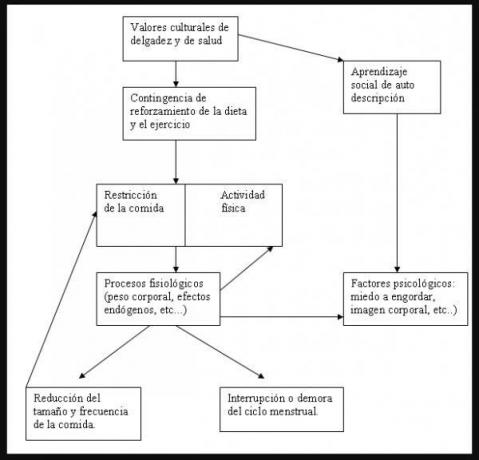

- Biobehavioral model of anorexia (Epling and Pierce, 1991) This model presents improvements with respect to the previous one by presenting the existing relationships between the different components of the behavioral problem. Relate cultural events to scientific research.

The DSM IV criteria.

Referring to annex 1 where the DSM –IV criteria for anorexia and bulimia are collected, we propose a critical analysis of these criteria taking into account their lack of operationality and their ambiguity in their drafting.

In the first place, the necessary revision of the translation that of the criteria is carried out is proposed; terms such as leading to or the translation of i.e. (from the Latin ID EST), show a asynchrony in the interpretation of the criteria that can lead us to error in the difficult differential diagnosis of the client with problems related to food. Examining the ambiguities and inconsistencies the main problem that we observe is the way of understanding unnatural behaviors with food. This is due to the lack of operationalization that is observed in the definitions of the criteria.

Criterion A is ambiguous as to what should be understood by “refusal to maintain body weight”. This expression can be applied to many people who want to lose weight (in our society the majority) and do not have any problem in relation to the food, thus a person who follows a restrictive diet for a long time and loses a lot of weight as a result, as well as an intense fear of gaining weight, you may not receive the diagnosis of anorexia because you have not reached a body weight that is 85% of that expected for your age and height.

The DSM-IV does not indicate how to determine the presence of fear of gaining weight or obesity. It does not provide guidelines for the appearance:

- of the alteration of the assessment of their weight and body image

- and your general self-evaluation as a person.

These problems give rise to numerous changes at the endocrine level; the person responsible for amenorrhea is only one of them. Although in any case it does not make sense to consider it as an independent diagnostic criterion since it is a consequence of criterion A, of weight loss.

Regarding bulimia nervosa the definition of binge eating is imprecise and differs from the proposition for binge eating disorder without clearly justifying this difference. Indeed, the five proposed manifestations (see Annex 1) pose difficulties due to their ambiguity: it is not specified what speed of The intake is abnormal, neither how much is an enormous quantity of food, nor how the discomfort and guilt associated with the episode of binge.

One difference that we do not understand is why this guilt it is set forth as a criterion for binge eating disorder and not for bulimia nervosa. According to Walsh and Garner (1997), their introduction seeks to provide behavioral markers of binge eating episodes, as these subjects did not observe compensatory behaviors that perform such function. Compensatory behaviors will therefore serve as a reference to delimit a binge in those subjects who manifest it, an opinion shared by Schlundt and Johnson (1990).

At the same time, in the criteria and compensatory behaviors, fasting, the use of laxatives, enemas or physical exercise are not operationalized.

Criterion D does not include guidelines to relate the subject's assessment of her body with the general negative self-assessment as a person.

Functional analysis as an etiological model of anorexia and bulimia.

Traditionally, anorexia and bulimia nervosa have been proposed as mental disorders or illnesses that give rise to a series of symptoms or manifestations. But those symptoms or manifestation explain the true cause of the problem or are only limited to describe this without proposing a real and scientific explanatory element or elements of the cause or Causes. So the problem which is really: will be fear of getting fat (no, since that is only a symptom), it will be distorted perception body image (again a symptom). An illness it cannot be the same as the symptoms through which it manifests itself; then then who are anorexia and bulimia apart from their symptoms.

Anorexia and bulimia are A SET OF ARBITRARILY SELECTED EMOTIONAL BEHAVIORS AND RESPONSES, they are neither more nor less than that. The other are simple names with which we identify the symptoms but that is not more than a name (Carrasco, 2000). As Schludnt and Johnson rightly point out: “An eating disorder is a abnormal behavior pattern regarding food intake and the energy balance ”.

So we have to ask ourselves why people with this problem with food behave like this, and once we know the cause or causes and their consequences, we can consider the possibility of modify them.

The results of research carried out within the framework of behaviorism manage to give a scientific answer to this question (Carrasco T, 2000). For example, the person who binges or reduces their food intake in an alarming way or describes themselves as obese they do so because the consequences of their behavior report well-being and that is why they remain in the weather. For this reason, as Carrasco, T (2000) says “the main task of the clinical psychologist is to find out what these consequences are and act on their cause”.

In short, the function of behavior is to facilitate the exposure of the subject to certain consequences and from there the functional analysis is derived.

We propose a review for any of the possible causes of "anorexia and bulimia nervosa" and its scientific explanation. Of course, not all functions will appear in all cases; some will intervene in some and others will intervene.

It is therefore not a matter of establishing treatment programs applicable to any person with an unnatural relationship with food, but rather of defining operationally the client's behaviors and the consequences that fall on her emotions (these emotions in terms of reinforcers will maintain or eliminate that behavior). Thus we will save techniques that do not have to be applied since the client does not need them. In summary, support in functional analysis is essential to determine the causes of the behavioral problem labeled "anorexia or bulimia nervosa."

Functions of reducing food intake.

- Avoid obesity. Being fat is associated with a large number of aversive consequences, thus facing the Anticipation of this behavior avoidance behaviors such as stopping eating, practicing exercise etc. This process is similar to a phobia in which avoidance behaviors reduce the anticipatory anxiety of the fear of gaining behavior. This function would be the most widespread and where most errors occur since it is thought that all girls have fear of gaining weight when now we will see that it does not have to be this way but that food is a means to get another conduct.

- Lose weight - look slim. The pleasant emotions that contemplating yourself thin provide easy access to frequent and intense reinforcers. (Carrasco, T 2000). The degaldez acts as a stimulus before which is followed by a positive reinforcer with which the conditioning is clear and their immediate learning related behaviors that lead them to access thinness and, in turn, reinforcers positive.

- Feel in control. It is a sensation that is experienced when verbal descriptions of a behavior are transformed into motor movement in relation to the environment. The feeling is nice. Food-related behaviors are important sources of control and the achievement of these elicit a well-being response by feeling the ability to control the behavior in this case would feed. In this role of unnatural behavior with food, hunger would act as a potent positive reinforcer that would reward your sense of control, contingency expectation of reinforcement of leanness and the non-appearance of obesity would in turn act as a negative reinforcement of the feeling of control. This can be operationalized, for example, with the kilos that the person is losing, which would also negatively reinforce the feeling of control.

There are more positive reinforcers of the previously mentioned behaviors; Thus, for example, we find ourselves with the care that the patient is going to receive, assume the role of person sick, and the avoidance of undesirable behaviors due to the fact of having a relationship problem with food.

We have described the functions that most frequently explain unnatural relationships with food, their initiation and maintenance; to finish inviting the design of treatments tailored to the client after the identification of the functions of unnatural behaviors with food that occur in each particular case (Carrasco, T 2000).

Annex 1: diagnostic criteria.

* Criteria for the diagnosis of F50.0 Anorexia nervosa [307.1]

- Refusal to maintain weight equal to or above the minimum normal value considering age and height (p. e.g., weight loss resulting in a weight less than 85% of what is expected, or failure to achieve weight gain normal weight during the growth period, resulting in a body weight less than 85% of the weight expected).

- Intense fear of gaining weight or to become obese, even while being underweight.

- Alteration of the perception of body weight or silhouette, exaggeration of its importance in self-evaluation or denial of the danger posed by low body weight.

- In postpubertal women, presence of amenorrhea; for example, absence of at least three consecutive menstrual cycles. (A woman is considered to have amenorrhea when her menses appear only with hormonal treatments, p. g., with the administration of estrogens.)

Specify the type:

Restrictive type: during the episode of anorexia nervosa, the individual does not recur regularly

bingeing or purging (p. e.g., inducing vomiting or excessive use of

laxatives, diuretics, or enemas)

Compulsive / purgative type: During the episode of anorexia nervosa, the individual

You regularly binge or purge (p. eg, inducing vomiting or overuse

laxatives, diuretics, or enemas).

* Criteria for the diagnosis of F50.2 Bulimia nervosa [307.51]

- Presence of Recurring binges.A binge is characterized by:

- (1) food intake in a short period of time (p. g., in a period of 2 hours) in an amount greater than what most people would ingest in a similar period of time and under the same circumstances

- (2) feeling of loss of control over food intake (p. (e.g., feeling of not being able to stop eating or not being able to control the type or amount of food being eaten)

- Inappropriate compensatory behaviors, repeatedly, in order not to gain weight, as they are provoking vomiting; overuse of laxatives, diuretics, enemas, or other drugs; fasting, and excessive exercise.

- Binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors occur, on average, at least twice a week over a 3-month period.

- The self appraisal it is exaggeratedly influenced by body weight and shape.

- The disturbance it does not appear exclusively in the course of anorexia nervosa.

Specify type:

Purging type: During the bulimia nervosa episode, the individual regularly induces vomiting or uses excessive laxatives, diuretics, or enemas.

Non-purging type: During the episode of bulimia nervosa, the individual uses other inappropriate compensatory behaviors, such as fasting or strenuous exercise, but does not regularly induce vomiting or use laxatives, diuretics, or enemas in excess.

This article is merely informative, in Psychology-Online we do not have the power to make a diagnosis or recommend a treatment. We invite you to go to a psychologist to treat your particular case.

If you want to read more articles similar to Etiology of Anorexia and Bulimia Nervosa, we recommend that you enter our category of Clinical psychology.

Bibliography

- Turon, G. (1997). Eating disorders. Barcelona: Masson.

- Saldaña, C. (1997). Intervention techniques in eating behavior disorders. Anxiety and stress, 3, 319-337.

- Fairburn, C. G. (1997). Eating disorders. In D. M. Clark and C. G. Faiburn (Eds.) Science and practice of cognitive behavior therapy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schlundt, D. G., and Johnson, W. G. (1990). Eating disorders. Assessment and treatment. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

- Walsh, B. T., and Garner, D. M. (1997). Diagnostic issues. In D. M. Garner and P. AND. Garfinkel (Eds.), Handbook of treatment for eating disorders. Second edition. New York: Guilford.

- Carrasco, T.J. (2000). Course material on the treatment of anorexia and bulimia nervosa organized by the Altair Psychology Center.