The term of specific language disorder was born in conjunction with a referral for aphasic disorders in adults. Gradually it has been displacing other more classic ones, such as alalia, audiomudez, congenital verbal deafness, evolutionary aphasia and dysphasia. This Online Psychology article offers a detailed study so that you can know what is the definition and causes of Specific Language Disorder where, also, you will find 4 studies that have been carried out on this topic.

Index

- What is Specific Language Disorder

- Identification criteria for specific language disorder in children

- Bottom-up orientation

- Study # 1: van der Lely and Howard (1993)

- Study No. 2: Botting and Conti-Ramsden (2001)

- Study # 3

- Study # 4: Montgomery (200)

- Conclusions on Specific Language Disorder

What is Specific Language Disorder.

The most characteristic definition about Specific Language Disorder comes from the ASHA (American Speech- Language- Hearing Association, 1980):

A language disorder is the abnormal acquisition, understanding or expression of spoken or written language. The problem may involve all, one or some of the phonological, morphological, semantic, syntactic or pragmatic components of the linguistic system. Individuals with language disorders often have language processing or speech problems. abstraction of meaningful information for storage and retrieval by short memory term.

As can be seen from the definition, SLI is not a clinical category as a global categorization (Aram, 1991), but rather a conglomeration of subcategories or subgroups with different possible causal factors. This leads us to wonder if the term SLI encompasses a number of different disorders.

TEL in children

At present the problem is approached from the heterogeneity of the TEL population (Mendoza, 2001). Specific language disorder is a disorder that affects a number of children who ranges between 0.6% and 7.4%, these differences obeying the criteria for classifying them and the age of the children themselves.

One of the problems we encounter when referring to the TEL population consists of not knowing what type of children, with what problems and with what linguistic profiles we are referring. To help us in this task they have proposed a set of identification criteria.

Identification criteria for specific language disorder in children.

On the one hand there are identification criteria by inclusion and exclusion that refer to the minimum requirements that an individual must have to be included within the population TEL, or on the contrary, the problems and alterations that must be presented to identify an individual as TEL.

- According to him inclusion criteria Children with a minimal cognitive level, that pass a hearing screening in conversational frequencies and do not present a brain injury or an autistic picture.

- On the contrary, if we rely on the exclusion criterion Individuals with mental retardation, hearing impairment, severe emotional disturbances, abnormalities will not be part of TEL orophonatory signs, clear neurological signs, or language disorders caused by adverse sociocultural and environmental But it is not possible to be so blunt, since the coexistence of SLI with mental retardation, with hearing loss and with other disorders has been proven.

Criterion for discrepancy

Another criterion used is the discrepancy where it is assumed that children with SLI must have the following characteristics:

- A 12-month difference between mental or chronological age and expressive language

- 6 months difference between mental or chronological age and receptive language

- o 12 months difference between mental or chronological age and composite linguistic age (expressive and receptive language).

TEL can be identified based on its evolution which is a great obstacle since we give it the character of durable and resistant.

Criterion for specificity

The last criterion used to identify TEL is the criterion for specificity It is understood that children with SLI cannot present other pathologies and the normality of SLI individuals is assumed in all aspects except linguistic.

This criterion is the one that gives rise to a series of investigations in which the working memory focus of interest of this work is framed. The first investigations on the presence of certain cognitive deficiencies in SLI children derived from Piagetian studies on logical or operative thinking. In all of them, a series of non-standardized cognitive tasks were used where verbal requirements were minimal.

The children presented a significant delay in operative taskssuch as spatial problem solving, number tasks, logical reasoning, and imaginative reasoning. In these first steps in the search for a cognitive deficit, it was not possible to establish a deficit table that would explain the language disorder in SLI.

Bottom-up orientation.

The next generation of cognitive studies in SLI children is defined as bottom-up orientation in which it is assumed that functions considered superior, such as language, are affected and depend on the operation of other more basic functions and psychologically less complex as they can be, memory, attention ...

The relationship between perceptual processing and SLI has been investigated, finding a difficulty in these children to differentiate sounds of short duration and rapid sequence. TELs are also slowed down in naming, word evocation, and non-linguistic tasks. (Mendoza, 2001) Language disorders have also been related to memory. SLI children have been seen to present problems at the level of working memory, which is a part of the short-term memory that is involved in the processing and temporary storage of the information.

Baddeley and Hitch (1974) suggest that working memory plays an important role in support of a wide range of daily cognitive activities, including language (Gathercole and Baddeley, 1993). The relationship between working memory and language is confined to the assumption of the need to process linguistic information input and store them for a period of time to be able to cope with the linguistic input and thus arrive at a correct understanding.

A failure in this system, whether for storage or processing of linguistic information, in this case would lead to problems in understanding. In an attempt to clarify to what extent working memory is affected in SLI children, studies have been carried out to determine the ability of these children to cope with tasks that require information processing and storage linguistics.

Below are a series of studies that attempt to clarify the situation of TM in these children.

Study # 1: van der Lely and Howard (1993)

The first study that is reviewed is proposed clarify whether children with SLI have a language impairment or memory deficit short-term (van der Lely and Howard, 1993). The previous literature shows us studies such as that of Kirchner and Klatzly (1985) which investigated with verbal trials in TEL children and compared this performance with a group of age-matched children chronological. The items are presented to them and the children rehearse each item out loud.

From the trial phase to the recall execution phase, 12 variables were evaluated, such as retention and order of items, semantic organization, repetition, and error intrusion. The predominant difference between TEL children and the control group was in the capacity of retention and regeneration of items and intrusion of errors, which the authors interpreted as that the TELs differ from the controls in their capacity in short memory term. Doing a more detailed analysis, it can be said that these findings are produced by a decrease in verbal ability in CPM.

These same authors continued with another study in which they investigated the speed of memory to register, to try to specify more precisely the focus of the deficit. For this, the child has to identify if an item appeared in a list of digits that has been previously presented verbally. The speed of saying yes or no provides the measure of speed of the record.

This study showed that TEL children are four times slower in the MCP registry than their peers with normal linguistic development (Kirchner and Klatzky, 1985). Comparisons of TEL children with children matched in language skills reveal areas that are disproportionately impaired in relation to their general level of language development (Bishop, 1982).

Another previous study to be discussed is the one carried out by Gathercole and Baddeley (1990) in which they compared a group of TEL children with a control group of normal children matched on a test of simple word comprehension and reading skills. They found that the TELs were deteriorated in repetition of pseudowords (phonological working memory). For many years the importance of language impairment in relation to the expressive language of TEL children has been emphasized. Recently, the interest in receptive language of these children has been increasing.

These investigations, like those that have studied expressive language, have found strengths and weaknesses compared to age-matched control children. Van der Lely and Haward (1993) studied linguistic representation and processing in relation to the MCP of the TEL children compared with children equal in age and whose linguistic stage was similar.

It is well known that children at different levels of development use different strategies to complete experimental tasks, these differences in execution, both in language tasks and in tasks MCP should reflect the use of different underlying language processes, at different stages of the growth. This comparison, the authors argue, is better because it reveals specific deficit areas and select individuals who are disproportionately impaired relative to their levels of language development general. In contrast, a comparison carried out only with control children of the same age with normal development reveals little about the nature of the linguistic impairments of the TEL population since TEL children will always perform tasks in which linguistic development is seen below wrapped.

The language impairment of TEL children must interact with different components of language and it can also affect many, if not all, language functions to some extent. It is intended to answer the following questions in the study by Van der Lely and Howard (1993): Does the Performance of tasks in the CCM of children with SLI differs from that of their peers in linguistic? If so, does the pattern of performance across multiple tasks differ for children with SLI compared to their peers? This study compares the MCP of TEL children (identified by the inclusion criteria) and controls matched in age and in a series of language measures (LA). The tasks used were repeating lists of words and pointing to a drawing.

In this study, the linguistic characteristics of the test stimuli were designed to explore the influence of semantic, lexical, and phonological similarity on PCM. The repetition paradigm requires verbal output, storage, and processing. The pointing response requires only storage and processing but no verbal output. It is hypothesized that if any of these three processes (semantic, lexical, or phonological) were involved in immediate recall, then recall of similar words (semantically, lexically or phonologically) should be poorer than recall of non-words related. Therefore, if TEL children were using either of these two processes to a greater extent than normal children, then differences would be appreciated between the two groups.

The study is divided into three experiments:

Semantic cognitive processing

He compared the recall for similar and semantically non-similar words. Baddeley found that recall was worse for semantically similar words than for unrelated words for both immediate and delayed recall. If SLUs are using semantic processing in the MCP for word recall, there must be differences between the two groups in the performance of recall tasks.

There were two tasks: one was asked to repeat the words from a list (repetition paradigm) and in the other to point out the words in a drawing, which the examiner previously said. It was also taken into account whether the memory was ordered or not in both tasks. The results of the experiment indicate that the TEL children appear to be running at a similar level and in the same direction as the normals matched in understanding and expression of the language. This suggests that TELs do not depend more on the semantic processing of words than their peer controls.

Effect of lexical processing

The effects of lexical processing and representation on immediate serial recall in TEL children and controls are explored. The execution in sets of words and pseudowords was compared. It was predicted that if lexical knowledge were used to facilitate recall, execution with pseudowords should be poorer than with real words. In both groups the words were remembered better than the pseudowords, this means that both groups were sensitive to the characteristics of the material.

This experiment demonstrates that for immediate recall of unrelated words and pseudowords, TEL children perform similarly to controls. This finding contrasts with other research that finds that SLI children are impaired in immediate recall of words compared to their age-matched controls (Kamhi & Catts, 1986).

Phonological processing

Phonological processing in MCP in SLI children was investigated by comparing the performance in immediate memory of unrelated and phonologically similar words using both the repetition and pointing paradigm drawings. It was found that phonologically related words and pseudowords were remembered worse than those that were not. This effect has been attributed to the separation of the components of the PCM: the articulatory loop and the phonological store. This experiment is aimed at investigating the storage ability of the phonological MCP of the TEL but not of the articulatory loop.

The effect of phonological similarity was significant for both paradigms. Low performance is reflected for phonologically similar words. The two groups appear similar in their memories of materials in the two paradigms. TEL children and controls appear to be affected in the same way by the phonological characteristics of the materials. This indicates that TEL children have a capacity for phonological material and a similar storage for such material as control children.

To summarize the findings we will say that the memory is not significantly but in the related lists than in unrelated ones in CCM tasks using either a point-to-picture response paradigm or a repetition paradigm verbal. Execution is better for real words than for pseudowords in the repetition paradigm. For the items presented aurally, sensitivity to the acoustic phonological nature of the materials was found for both paradigms, in which the memory immediate processing and storage is involved, indicating the linguistic phonological nature of the short-term store for the sounds of the speaks.

TEL children generally performed at a similar level, and were equally sensitive to how they responded to the task and to the linguistic demands of the task. In the tasks of pointing to the drawing there are no differences between the execution in the two groups, but for the paradigm of repetition in all cases the memory of the children TEL was below the controls for the ordered memory of the items. One possibility is that these differences between TEL children and controls may reflect small differences in output processing or at higher levels of representation, as has been suggested in research of children with phonological problems.

It is worth mentioning with special interest that although no differences were found between the groups in the tasks of MCP, in the TEL, a significant deterioration was found in comparison with the control group in a number of tasks linguistics. The data from this study suggest that the hypothesis cannot be generalized to all SLI children as a whole. On the other hand, the data suggests that TEL deficit in children is not general in nature rather, it is confined especially to linguistic and / or representational processes.

Finally, we will point out that these results, that the TEL children do not differ significantly from the controls in terms of repeating lists of pseudowords implied by phonological TM (van der Lely and Howard, 1993) seem to contradict what other findings say (Gathercole and Baddeley, 1990). In this study it is seen that children with language disorders show significant impairment in the repetition of simple pseudowords, particularly when they had 3 or 4 syllables. One possible reason for these differences is that there must be differences in what is required in repeating tasks of a short or long list of pseudowords.

Study No. 2: Botting and Conti-Ramsden (2001)

The second study that we will review aims to account for the relationship between the performance of SLI children in TM phonological (repetition of pseudowords) with the index of current language and the ability to read and write (Botting and Conti- Ramsden, 2001).

The pseudoword repetition task has been criticized for suppressing one of the TM components, processing. The study was carried out with two groups of TEL children, one of them with a high score on a pseudoword repetition task and the other with a low score. The phonological TM of both groups is measured with the Pseudowords Repetition Test for Children (CNRep); language (grammar, use of verbs in the past, use of third person verbs) and reading skills (basic and comprehension). Children aged 7 and 11 are measured, skill development is also taken into account.

The results are the following:

- To age 11 years In the high CNRep group and the low CNRep group, there are significant differences in the tests that measured language. Scores in both basic and comprehensive reading also differed significantly between the groups. These therefore reaffirm the association between phonological processing and reading skills. Through development you also find this association (change from 7 to 11 years).

- To age 7 years He is given assignments of naming vocabulary and reading simple words, articulation test, and the bus history test. Differences between the two groups (high and low CNRep) are observed in simple words and articulation. To evaluate the change that occurs from 7 to 11 years, the Test for Grammatical Reception (TROG) is passed, simple reading of words and expressive vocabulary. The findings indicate a clear relationship between performance on pseudoword tasks and current language ability.

Vocabulary measures, however, were not as clearly associated with pseudoword repetition at the age of 11 or 7 years in terms of skill progression. On the other hand, the grammatical ability measures (phrases in the past, use of verbs in the third person singular, the TROG) did show significant differences regarding the level of execution, according to the ability to repeat pseudowords of the groups (high or low score in CNRep). This association also occurred in the progress of receptive grammar skill from the age of 7 to 11 years.

This suggests that verbal ability is woven into Verbal Short Term Memory, not simply in terms of phonological outputs but also in terms of the development of more complex skills. It is therefore evident that the repetition of pseudowords is a good task to detect children with SLI. But one wonders if this task will also detect children who have improved their language skills over time, that is, if it can identify subclinical impairments.

The authors found that the tasks in which the CCM is involved, such as the repetition of pseudowords or the recall of phrases, was superior for evaluate syntactic skills that will identify groups of children with a history of SLI in adolescence, that is, when language ability has improved. Finally, it is hypothesized that the nature of memory deficits in SLI children is determined by their inability to maintain phonological representation in TM. This should explain why the groups do not differ in non-verbal memory tasks.

Study No. 3.

Linking with the above, that the groups do not differ in non-verbal memory, we could ask when this point if the TEL children do not in fact show problems in the visuospatial component of working memory (MT). The next study I am going to present aims to examine whether relationship between language and memory it extends through the processing domains of the visual spatial component of TM.

This study is done with children who are matched in cognitive ability but different in their ability to repeat pseudowords, that is, in terms of phonological TM. It is intended to find out that 4-year-old children with a relatively good ability to repeat pseudowords will produce spoken language with a more diverse repertoire of words, longer sentences, a wider range of syntactic constructions, than children with poor repeating ability pseudowords. It is also intended to determine if there is a significant association between phonological TM and unspoken response. and language, it will be concluded that the hypothesis of "mutual exit constriction" is not the only source of the relationship.

This hypothesis predicted that if phonological outputs were intervening in the process of speech production, a weaker relationship between language measures and visual memory load evaluated with non-speech, than with a spoken recall process. And finally, it will be seen if the relationship between language and short-term memory extends beyond the retention of verbal information, that is, to visuospatial information. It is expected to find a comparable relationship between language skills and short-term visuospatial memory skills and phonological memory performance.

The subjects that make up this study are two group of 4 year old children, with good or bad ability to repeat pseudowords (phonological TM), and both were evaluated with a measure of general intelligence (Raven's progressive matrices).

Verbal memory is measured:

- Pseudoword repetition with the Pseudowords Repetition Test for children (CNRep). Memory for familiar words with spoken and unspoken recall. The memory load of each child was evaluated for familiar words presented aurally. There were two sets of phonologically distinct words with simple syllables (consonant-consonant vowel).

- Memory for words with spoken memory. The memory load is progressively increased by adding an item to the list each time the child remembers the given list. It starts with two words and one word is added to each new list.

- Memory for words with unspoken memory. Children are shown a series of pictures, the experimenter names them. All the drawings are shown and the experimenter only names some of them, the child has to point out which of the pictures the experimenter has said. Later visual memory is evaluated: Corsi block. The experimenter hands a sequence of 9 wooden blocks on the table. The child has to replicate the sequence. It increases by one each time the child gives a correct answer for a block. Visual pattern loading. Finally the speech body is evaluated where the children are asked to elicit speech. Pictures are presented to him and the children have to say what is happening in them. This test looks at the mean length of the sentence and the use of syntactics, among other things.

The results are the following:

Regarding verbal memory load. Children with low pseudoword repetition recall fewer words than children with high pseudoword repetition with both response paradigms (speaking or pointing). As for visual memory. Children with high scores for pseudoword repetition also tend to remember more spatial information in the two visual memory tasks (Corsi and Visual Pattern) that children with low repetition scores pseudowords.

Comparing the groups, the children with high CNRep scores produced speech with a large number of different words and a larger phrase length in terms of mean number of morphemes per sentence. It also tends to score higher on the Syntactic Productions Index (IPSyn) on all its scales except in the use of questions and negative sentences. Regarding the verbal memory load, the execution in CNRep was significantly associated with the number of different words and with the morphological LMF in the speech of the children.

IPSyn is associated with the ability to repeat pseudowords. The memory load for familiar words with spoken memory is associated with the number of different words and with the morphological LMF and with the total IPSyn. Verbal memory load with unspoken memory significantly correlates with language. Regarding the visual memory load, the number of different words and the morphological LMF correlate significantly with the Corsi and also with IPSyn.

However, none of the language indexes correlate with visual pattern loading. Once the analyzes are done, we can say that the children classified with a good phonological memory in repetition tasks of pseudowords, produced a spoken language with a large number of words and with longer sentences than children with poor repetition of pseudowords. The same happened for syntactic constructions in speech. On the other hand, the hypothesis of "mutual exit constriction" was not true since it was found that the memory advantage persists in the group of children with good repetition of pseudowords not only when a spoken recall process is required but these advantages are maintained for when the answer requires no output verbal.

If, as has been verified, the association between language / memory is not eliminated when the output requirements of the task are minimized (only noting is required), this shows that the correspondence between children's CCM and their language development cannot be explained in terms of differences in articulation skills present in both memory tasks and spoken language tasks (Briscoe, et al, 1998).

On the other hand, it can be argued that the association between spoken language development and phonological memory ability must arise because both tasks share the same sets of cognitive processes. So phonological output processing skills should not be used for processing, operating only on phonological information (output mutual constriction hypothesis). But the results show that the association is also found with aspects of visuospatial MCP. The evidence of greater vocabulary production in children with better phonological memory ability reflects previous differences in vocabulary compression, therefore phonological memory is related to both production and comprehension (see Montgomery, 2000).

The restricted range of syntactic constructions found in children with poor repeating ability pseudowords agrees with the fact that a similar mechanism must operate in the acquisition of models grammatical. East impoverished use of the variety of grammatical constructions it should reflect the influence of phonological memory skills that are crucial in the imitation and retention of adult syntactic patterns. Another explanation is that the relationship between phonological memory and language development is influenced by rehearsal processes and speech planning.

In this study the advantage of children with good ability to repeat pseudowords can be explained for his ability to covertly rehearse, before recall, the items to be remembered. This explanation could be verified by examining the relationship between language and phonological memory ability in the unspoken recall paradigm when rehearsal is prevented through the use of suppression techniques articulatory.

Study # 4: Montgomery (200)

Finally, I will present a study by Mongomery (2000) that seeks to examine whether differences in comprehension of sentences in children with or without TEL are related to TM functional capacity. This study is presented in order to save the criticism that has been made to studies based on the repetition of pseudowords, criticism that says that one of the functions of working memory is consciously eliminated, that is, the prosecution.

Returning to the theme, functional capacity is conceptualized, according to Daneman, as the ability to store information in TM while simultaneously carrying out several processes of understanding the material. Therefore, storage and / or processing must share limited resources during comprehension. If the storage and / or processing demanded by a comprehension task exceeds the amount of resources available in MT, a disconnect can occur between storage and processing (Daneman and Merikle, 1996).

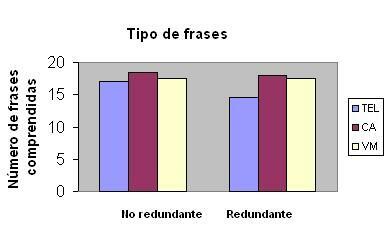

The study participants are three groups of children, some classified as SLL, one group matched in age (CA) and the other matched in receptive vocabulary (VM). There are two tasks, one specific for working memory and the other for comprehension.

In the working memory task there are three conditions: free recall (no processing load), simple recall (simple processing load where you are asked to remember the words according to an order from smallest to largest), and double memory (double processing load, words are remembered according to categories and according to the order that was exposed in simple memory).

The prediction that children with SLI show decrease in storage under both conditions of processing load compared to CA was partially corroborated. Children with TEL performed similarly to ACs in the no-load and single-load conditions, but a decline was seen in the execution of the double-load condition. CAs are not affected by the processing load. The VMs and TELs performed the tasks similarly under all conditions.

The execution of the TEL children in the no-load condition suggests that in the absence of additional processing, the child with SLI has a simple storage capacity comparable to that they have VM and CA. Running in simple load shows us that TEL and VM have some ability to coordinate storage and processing, but in a more demanding condition (double load) shows a decrease in storage. Therefore, TELs have less functional MT than CAs and an MT comparable to VMs. This poor performance of TEL children is explained by the difficulty these children have in keeping words in working memory, presumably because TM resources were not evenly distributed between storage (few resources) and processing (many resources).

Second study task

The second task was a task of understanding redundant and non-redundant sentences. After listening to them, the child had to match it with a drawing of 4 possible ones. The results were the following:

- TELs comprise fewer redundant and non-redundant phrases than CAs.

- VMs comprise the same number of redundant and non-redundant phrases, however TELs comprise fewer redundant than non-redundant phrases.

The poor understanding of redundant sentences by children with SLI, compared to VM, seems not to be attributable to the lack of syntactic knowledge, but due to the difficulty of maintaining the increase in verbal demands in TM, there are two reasons that corroborate: TEL and VM execute the non-redundant phrases the same, which were essentially the same syntactically as the redundant phrases. The TELs show worse execution in the redundant than in the non-redundant ones and the VMs show no preferences. The poor understanding of redundant sentences by children with SLI seems to reflect the difficulty these children have in storing more amount of input while simultaneously and rapidly computing the new syntactic and semantic representation of the information incoming. To support this interpretation the data show that TEL have more difficulty understanding sentences with a double subject, which sentences with relative subjects and in which they have less difficulty are in sentences with adjectives, adverbs ...

How can the findings that children with SLI understand fewer sentences be reconciled? redundant than their peer VMs with the findings that the two groups similarly ran the MT task? The answer appears to lie in the nature of the task and how children's intrinsic information processing skills interact with the task.

In the working memory task, children with TEL and VM are able to keep up with the demands of storage and processing. Apparently these united demands do not exceed the resources of the functional MT of the TELs. In contrast, the processing demands of the comprehension task evidently do. Children have to store and understand the incoming sentence and then select a picture that matches what they hear. But it is more likely that they too will have to generate a linguistic interpretation of each drawing, store each of these representations and then comparing each representation of the incoming phrase before giving a answer. These additional processing requirements should not only demand from the functional MT resources but also from its general processing capabilities.

Conclusions on Specific Language Disorder.

As we have been affirming throughout the work, individuals with SLI usually have language processing problems or abstraction of significant information for the storage and retrieval of the MCP. Within the CCM, the TEL children present problems at the TM level, which is involved in the processing and temporary storage of information. TELs have simple storage capacity and the ability to coordinate storage and processing but in the face of high demands on linguistic tasks, there is a mismatch between storage and prosecution.

It has been seen that TEL children differ from their peers in retention and generation capacity, they are slow in registering linguistic information in MCP and are impaired in pseudoword repetition which is a good task to detect SLI (MT phonological). This pseudoword repetition task has been related to the current language ability of TEL children, seeing that it is a good predictor of said ability and its progress, and with the number of different words that children emit, as well as the LMF and the productions syntactic. We cannot conceptualize the specific language disorder in a global way but its nature is confined to linguistic and / or representational processes.

It is postulated that memory deficits in SLI children are determined by their inability to maintain phonological representation in TM, since the execution of the TEL children is impaired when they have to carry out more than one process at the same time. Therefore, the evidence presented in the work not only has implications on the relative abnormality of the language development of SLI children, but also for the debate on the nature of impairments as a specific module or impairment in more general cognitive processing which is, however, crucial for the acquisition of the language.

This article is merely informative, in Psychology-Online we do not have the power to make a diagnosis or recommend a treatment. We invite you to go to a psychologist to treat your particular case.

If you want to read more articles similar to Specific Language Disorder: definition and causes, we recommend that you enter our category of Learning disorders.

Bibliography

- Adams, A.M. & Gathercole, S.E., 2000. Limitations in working memory: implications for language development. Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 35, 95-116.

- Aram, D.M. (1991) Comments on specific language impairments a clinical cathegory. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 22.84-87.

- Bishop, D.V. M. (1982). Comprehension of spoken, written and signed sentences in childhood language disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23, 1-20

- Botting, N. & Conti- Ramsden (2001). Non-word repetition and language development in children with specific language impairment (SLI). International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 36,421-432.

- Briscoe, J., Gathercole, S.E., & Marlow, M. (1998) Short-term memory and language outcomes after extreme prematurity at bith. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 41,654-666.

- Daneman, M., & Merikle, P. (1996). Working memory and language comprehension: A meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 3,422-433.

- Gathercole, S.E., & Baddeley, A.D. (1993). Working memory and language. Cambridge, UK, Essays in cognitive Psychology.

- Kamhi, A., & Catts, H. (1986). Towards an understanding of developmental language and reading disorders. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 51,337-347.

- Kirchner, D. & Klatzly, R. (1985). Verbal rehearsal and memory in language disordered children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 28,556-565.

- Mendoza, E. (2001). Specific language disorder (SLI). Madrid, Pyramid.

- Mongomery, J. (2000). Verbal working memory and sentence comprehension in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 43, 293-308.

- Van der Lely, H.K.J. & Howard, D. (1993). Children with specific language impairment: linguistic impartialment sentence short-term memory deficit? Journa.